Reflections on Cambodia: Beautiful People and a Dramatic History

- Charlie

- Apr 8, 2024

- 7 min read

Dear Friends,

I write to you today from Koh Rong Sanloem, a tropical island off the Coast of Cambodia in the Gulf of Thailand. It’s a rainy morning here at my temporary home for the last 8 days, hence why I am writing to you rather than soaking up the sun. The island is composed of small, idyllic beaches flanked by thick green jungle. Snorkeling over breathtaking coral reefs during the day and bio-luminescent plankton at night compliment hammocks on the beach and a tranquility that I’ve experienced in few places I’ve traveled to. Currently the only accommodations are small sustainable beach bungalows which are accessible at $10-60/night.

But this peaceful natural beauty is sadly not destined to last much longer. The Cambodian government and Chinese resort enterprises have announced luxury beach resorts, a casino, waterpark, zoo, golf course, and shopping center, all of which will completely transform this small natural paradise into a Chinese Miami Beach. The less ‘desirable’ parts of the island have been gifted by government leaders to friends, a corruption story so common in Cambodia that locals just shrug at the suggestion that anything is amiss. Because in comparison with Cambodia’s recent history, ecological destruction for the benefit of those in government is nothing out of the ordinary.

But there was a time, before the horrors of the 20th Century plunged the country into chaos, where Cambodia did not rely on foreign investment and tourism to grow its influence and economy.

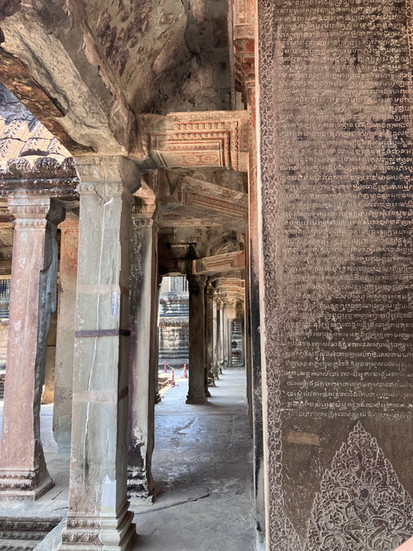

My first week here was spent in Siem Reap, home to Cambodia’s famous Angkor Wat temples. Angkor Wat itself is one of 50 temples built by the Khmer empire between the 9th-15th Centuries. The city of Angkor Wat was once one of the largest population centers in the world, when the Khmer empire stretched from the beaches and jungles of Eastern Burma (today Myanmar) to the Southern-most reaches of the Mekong Delta (today Vietnam). It was initially a Hindu empire but converted to Buddhism in the 12th century along with most of Southeast Asia. However, later Buddhist temples still include Hindu themes and Gods alongside Buddhist ones. I visited 12 temples in total including the most famous Angkor Wat, Bayon, Ta Prohm, and Banteay Srei. The stone mason work on these structures is a sight to behold, and it’s mind-boggling to imagine how they were built at a time before modern tools. The Khmers had one of the most impressive empires in Southeast Asia, yet Cambodia has since been in a downward spiral that it has only recently started to correct.

After Cambodia gained independence from France in the 1950s, the country was ruled by Dictator Prince Sihanouk, whose principal achievement was keeping Cambodia neutral during the Vietnam war. But in 1970 he was deposed by a coup d’Etat, and was replaced by his Prime Minister Lon Nol who attempted to establish a republic and immediately declared war on Vietnam, making the disastrous mistake of assuming that the US would come to Cambodia’s aid. On the contrary, American public opinion had turned decidedly against interventionism in Indochina and President Nixon’s only interest in Cambodia was limited to bombing the Vietcong on the Ho Chi Minh trail.

Meanwhile, farmers along the nation’s Eastern border gradually began to join Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge communist ethno-nationalist guerilla force, modeled after the Vietcong. In 1975, having defeated Lon Nol’s army, the Khmer Rouge marched into Phnom Penh, evacuated city residents to collective farms in the countryside, and began a rampage of ethnic cleansing that led to around 2 million deaths over almost 4 years.

In Phnom Penh I visited the old Khmer Rouge S21 Prison and Killing Fields. S21 was one of Pol Pot’s most important prisons where he detained Cambodian ministers and intellectuals along with foreigners during his reign of terror from 1975-1979. Thousands were detained there, all but 11 were tortured and killed for being ‘enemies of the state.’ People were detained for wearing glasses, having a university degree or just being a ‘city person.’ Walking through the prison, I found myself face to face with the pictures of soldiers and detainees taken on their arrival at the prison. It is impossible not to cry when confronting these faces which portray every shade of terror or resignation at their impending fate.

The Killing Fields is a mass grave site outside of the city where people were sent to be killed in the middle of the night. Men, women, and children were murdered by brainwashed teenage soldiers using metal tools. Thousands of people were buried in mass graves and to this day every rainy season brings more bones, articles of clothing, and other remains to the surface. It’s also possible to view the ‘killing tree’, where babies were murdered by soldiers who smashed their heads into its trunk.

But despite reports of these atrocities reaching the west, the US and its western allies stood by and watched the Khmer Rouge genocide from the sidelines, and even recognized Pol Pot as the sovereign leader of the country. All of a sudden communism in Indochina wasn’t an American concern anymore, even after the US military had come in and destabilized the region through $176 Billion worth of bombing and combat troops in Vietnam. It wasn’t until Vietnam invaded Cambodia in January 1979 and overthrew Pol Pot that the international community began to recognize what had happened there.

Visiting these sites today in 2024 given the current situation in Gaza makes for an especially sobering experience. At this very moment, we are also living in a time of genocide. Horrible civilian killings are happening in Gaza in part because of US funding and diplomatic support to Israel. I, like most people, have been sitting on the sidelines watching as my tax dollars are funding this war. It makes me sick to learn about the history of genocide in Cambodia while today a similar story is playing out in the middle east.

Perhaps if anything can come close to rivaling the horrors of genocide, it is the long-lasting legacy so much destruction leaves behind. Today Cambodia is moving on from the 20th century, but the effects of the Khmer Rouge can still be felt 45 years after it ended in 1979. I could feel this most clearly in conversation with my Cambodian friends.

After leaving Siem Reap, I got to travel to the village Ou Reang Ov to meet and stay with the family of my friend and former boss Savon from ECC Thailand school. Her parents are both in their 80s but are in good health and continue to work on their farm growing mangoes and bananas. Even though they speak zero english (and I speak zero Khmer), we got to know each other through Savon/Google translation as well as many hours of hand gestures. Kind of like playing charades except the stakes are much higher!

Savon’s family has been living in Ou Reang Ov for well over 200 years. Ou Reang Ov is a tiny village on the east side of the Mekong river, north of Phnom Penh and only one hour from the border with Vietnam. The lower Mekong river Delta has been contested between Khmer and Vietnamese empires for centuries. During the Vietnam war, Cambodia’s border with Vietnam was used frequently by the Vietcong to aid missions against South Vietnam as well as train Cambodian leftist guerrillas. Savon’s father was one of the farmers swept up in the tidal wave of recruitment during the years before Pol Pot took power. He told me he drove supply trucks for the Khmer Rouge army during the resistance years and shortly after Pol Pot took Phnom Penh in 1975, when Savon was born. As the brutal mechanisms of the Khmer Rouge regime became more apparent, he took his family and fled to the jungle. He says that now he is at peace with this past and is a devout Buddhist. Like most people, he looks back on the Khmer Rouge as a traumatic period of life, one in which he lost many cousins, nieces, and nephews.

Back in Phnom Penh, I met up with my friend Ti. Ti speaks fluent English thanks to his upbringing in Phnom Penh and education at NYU. He shared with me his family’s story of the Khmer Rouge while we ate noodles in a small restaurant across the street from the National Museum. Ti’s family are of Chinese background, and moved to Cambodia from China in the 19th century. He told me of the hardship his grandparents and great-grandparents experienced. I was shocked to learn that they managed to survive given that the Khmer Rouge regime was intent on ‘cleansing’ the country of non-Khmer ethnic groups. Luckily, Ti’s family spoke fluent Khmer and were not of the educated/wealthy class so they survived. Walking around after our lunch Ti pointed out a group of children walking around wearing identical shirts, he told me this is because the children are part of an orphanage. It’s quite common for parents who struggle to support their children to send them to orphanages. It’s more socially acceptable to do this in Cambodia because so many people lost their parents and were orphaned during the Khmer Rouge. The generational trauma caused by genocide is still playing out across the country.

After the Khmer Rouge, Cambodia was occupied by Vietnam until the end of the Cold War. Since then it has been ruled by the iron fist of former Khmer Rouge member Hun Sen and now his son Hun Manet. While Cambodians finally know peace, the country suffers from widespread corruption and a struggling economy. While de-mining efforts are making progress, anti-personnel and anti-tank mines still kill or maim rural farmers every year. The Cambodian government regularly grants timber contracts to foreign companies and looks to grow Chinese and western tourism wherever it can to line its own pockets.

Which brings me back here, to Sunset Beach, a place that won’t exist in the same way two years from now. While life for Cambodians has improved many magnitudes from where the country was half a century ago, destruction continues on the ecological scale. But who am I, an American backpacker paying $12/night for a bed in a bunkroom on the beach, to tell Cambodians what their government should or shouldn’t do for their economy?

Nevertheless, it’s easy to see how building masses of luxury development is a short term money grab to the long term ecological detriment of the very resource Cambodia is trying to monetize. Yes, Chinese tourists bring in more money than western solo backpackers. But money for who?

I can only hope that the answer is for all Cambodians.

Because if anyone deserves some peace and financial security, it’s the hopeful and friendly Cambodians on the street, in the fields, and small villages who seem to appreciate the simple pleasures after generations of trauma and anguish. I’ve been welcomed with open arms everywhere I’ve traveled here and I feel so grateful that I had the opportunity to visit this beautiful, if troubled nation.

Looking out at the sand, waves, and dense jungle around me, I want to remember Sunset beach just as it was: a serene natural paradise. In this alternate reality, the developers and tourists are far away and the days are still marked by only the sound of crashing waves, wind in the trees, and the distant chirping of birds and crickets as the orange sun sets, sending pink streaks across the sky.

Comments